Introduction

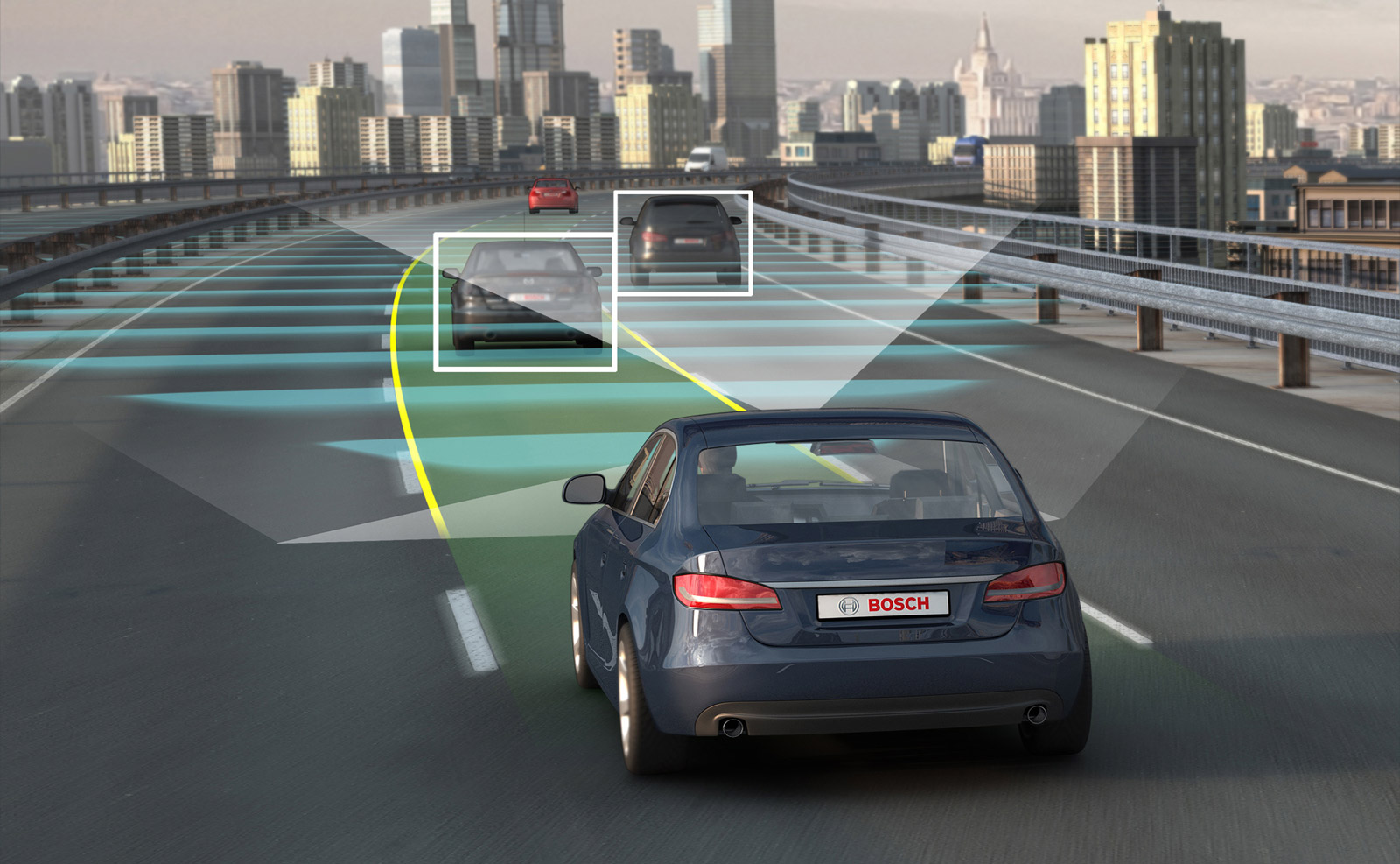

This article presents the risks to which users of autonomous/connected vehicles are subject, concerning the Information Security. It will be shown that it is possible to obtain unauthorized access to the Electronic Control Units of vehicles, pointing the importance of concern for producers, to the extent that this can bring impacts the lives of millions of people.

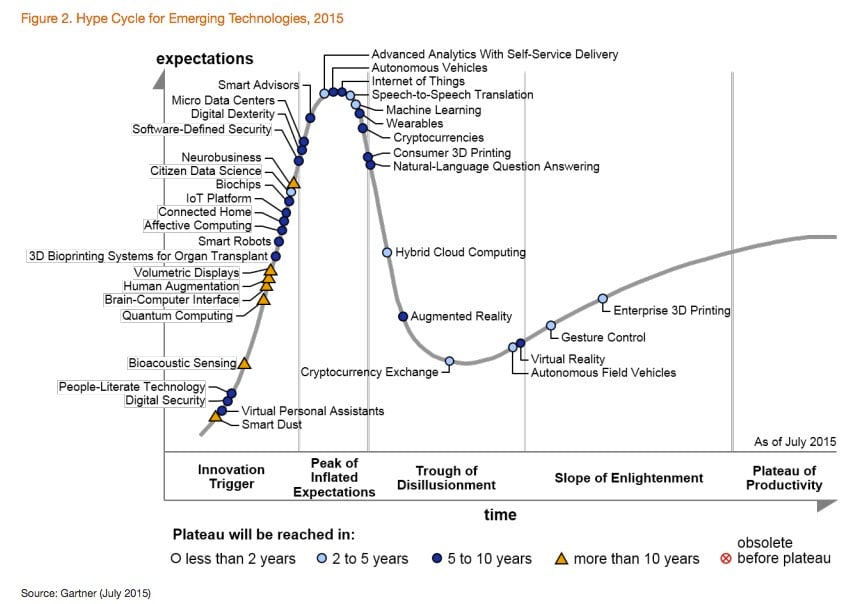

From the industrial revolution, humans began to automate tasks previously performed manually. Since then, these activities have spread among several segments from a remote control to a digital worksheet. That said, we are in an increasingly digital society, overwhelming the barrier of 5 billion devices connected to the Internet and estimated to reach 25 billion in 2020 (Gartner, 2015a). According to Forbes (2015), by the year 2020, more than 150 million vehicles will have an Internet connected module; which is usually called the “connected vehicle”. Furthermore, 2015’s Hype Cycle pointed out autonomous vehicles as a promising technology for years to come (Gartner, 2015b). However, issues that compromise the three pillars of Information Security (Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability) must be better studied because the countermeasures used by manufacturers (considering the literature) are not able to mitigate the risks (ABNT, 2013). As an example, researchers have obtained remote access to Jeep brand vehicles and control various mechanisms (Wired, 2015).

AUTOMOTIVE NETWORKS

Because of the large number of electronic control units (ECU) incorporated in a vehicle, the exchange of information between them through dedicated connections appears unfeasible, due to physical space and cost. To overcome this problem, most of the ECU is connected to a bus which transmits messages to all its nodes. A vehicle therefore has a number of interconnected subnetworks (Blommendaal, 2015).

CAN

According to Davis et al. (2007), the Controller Area Network (CAN), initially designed in 1983 by Robert Bosch, is a serial bus communication designed to provide simple, efficient and robust communications for automotive networks. First appeared in Mercedes S series in 1991. It enables connections up to 500 Kbit/s.

LIN

Local Interconnect Network (LIN) is a low cost bus, aimed at non-complex tasks such as the operation of windows, electric mirrors and lighting (Blommendaal, 2015).

FlexRay

The FlexRay is an evolution of CAN and LIN, driven by increasing demand for operations that require higher bandwidth and can achieve throughput of up to 10 Mbit/s. The applications most suitable for its use are: ABS, engine management, brake, suspension and transmission (Makowitz, Rainer, and Christopher Temple, 2006).

MOST

The MOST technology is designed to support large volumes of data as required for audio and video streaming services (Blommendaal, 2015).

Most modern vehicles can receive information from external sources, such as removable storage devices and online services provided through 3G/4G networks. Another possibility is to OTA updates (Over-the-Air), where manufacturers offer software increments to fix bugs, reducing the need for the owner to take his vehicle to a dealership. Along with the entertainment and convenience enabled by these technologies, the internal vehicle network is potentially exposed to exploitation. Although the protocols implement some security mechanisms, they may prove ineffective face of most current threats.

CLASSIFICATION OF ATTACKS

Goals

Unauthorized modifications

The owner or specialized company may resort to adulteration of the ECU, in order to reduce values stored in the odometer, aiming their own benefit to sell the vehicle, for instance.

Sabotage

Any acts in order to impair the proper functioning of the vehicle and that could endanger the lives of its occupants. From low-risk operations, such as to prevent the closing of the windows or lock the windshield wipers breeze to extremely severe events, such as disabling the activation of the brakes.

Theft

When an attacker exploits a vulnerability in wireless communication protocol to disable the alarm and unlock the vehicle doors.

Privacy Leak

The issues involving privacy become very sensitive when we talk about autonomous vehicles. Considering that individual habits and even the location of freight vehicles will be subject to tracking, to the extent that coordinates can be exchanged between the car and located servers anywhere in the world. In this sense, there are three points to consider (Glancy, 2012):

- Where the module responsible for artificial intelligence is located (built-in or external to the vehicle)

- How the external information, as the ways in which the vehicle travels will be obtained

- Which vehicle data will be transmitted

An attacker can obtain the contact list and calls history of the vehicle and plan a criminal action from monitoring of GPS coordinates.

Vulnerabilities in communication

In Wolf, Weimerskirch and Paar (2004) CAN fails to provide key security properties of information:

- Confidentiality: architecturally, messages sent to the CAN are transmitted to all nodes. This favour the capture of traffic and viewing content by malicious individuals.

- Authenticity: the header of a CAN message does not include the authentication of its sender. Thus, any node can send all types of messages, even without permission.

- Availability: low computational power associated with CAN soft control rules make it relatively simple for an attacker to cause a denial of service.

- Integrity: the CRC (Cyclic Redundancy Check) is insufficient to prevent an attacker to send a malicious message, as it is simple to forge a valid CRC.

- Non-repudiation: currently, there are no methods to prove the receiving/sending a message by an ECU.

Internal Attacks

Although some security mechanisms are implemented in automotive networks, only recently this topic has received more attention as it grows connectivity.

Local Attacks

Through the OBD port (On Board Diagnostics), you can read and send packages. This interface is used in the diagnosis (generated from analysis of the vehicle sensors) problems presented by vehicles and became mandatory in cars sold in the US since 1996 and in Europe in 2001 (for the gas-powered). There are OBD connectors being marketed to the public, relying on Bluetooth interfaces, facilitating its integration with mobile applications. Using this port or through direct access to the desired module, it is possible to exploit. As seen in Koscher et al. (2010), some ECUs may have changed its instruction set, causing the engagement of the entire system. Nilsson and Larson (2008) showed the concept of automotive viruses, where an action is only triggered when a specific event occurs (exceeding a set speed, for example). It can be argued that for the execution of these attacks is necessary physical access to vehicle structures. However, because modern vehicles have wireless connectivity, this restriction ceases to exist, as will be seen below.

Remote Attacks

In Koscher et al. (2010) exploits have been reproduced without relying on physical access to the internal vehicle network. These attacks can be divided into three categories, according to the form of access: indirect, wireless short distance and wireless long distance.

Indirect access

It is based on device status and / or media that will be used later in the vehicle.

- Media Player: a vulnerability in decoding of media with WMA format allows for playback are issued arbitrary messages directly to the bus. This becomes a risk, as there are spread malicious files through peer-to-peer networks;

- USB: Similar to the above case, an user device (such as a smartphone or USB key) may contain malicious files. Another possibility is operating Bluetooth connection through an infected phone, for example.

Short distance

They may be of direct type, if the target is a communication module of the vehicle or indirect, when using a device already paired (such as a smartphone).

- Pairing mobile: the comfort provided by the Bluetooth activation to connect your smartphone to the vehicle and use the sound system to make calls without manual intervention also open up breaches where attackers can access data of the control units or the content of phone calls (Checkoway, 2011);

- Communication between vehicles: in the future, there will be communication between vehicles and infrastructure of roads. This will enable the notice about accidents, sudden braking or when approaching another vehicle at an intersection. On the other hand, it’ll also allow improper interception of communications and sending false information which may trigger an inappropriate reaction;

- Wireless unlocking: although there is an encryption procedure when the wireless unlocking of the doors and alarms, this encryption can be broken. This was demonstrated by Courtois, Bard and Wagner (2008) and Eisenbarth et al. (2008) through the use of algebraic techniques applied to KEELOQ® used in vehicles of brands like General Motors, Honda, Toyota and Volvo.

Long distance

- Telephone: in Checkoway et al. (2011), after the discovery of vulnerabilities in the phone module (which allows the vehicle automatic call in case of accident), it was possible to run a malicious code downloaded over 3G network, compromising the vehicle;

- Web browsing: if the vehicle has a web browser, should be considered the same types of attacks on personal devices. Among them: cross-site request forgery, buffer overflow, etc;

- App Store: applications can contain malicious code, deceiving users.

PROTECTION

Parallel to the examples of attacks that has been demonstrated, it is being developed countermeasures. However, some restrictions should be considered in the automotive context and, as a result, the technical study to enhance the security of their networks.

Restrictions

For the protection of the connected/autonomous vehicles is mandatory adaptation of traditional computer security methods, given the limitations imposed. Wolf, Weimerskirch and Paar (2004) presented the following restrictions:

- Hardware: ECUs have reduced processing power and memory capacity. That said, they are not able to perform advanced cryptographic operations, thus working with algorithms that offer low protection;

- Real Time: complex math calculations must be performed in fractions of a second to allow the decision-making of the connected/autonomous vehicles without compromising passenger safety. Therefore, security mechanisms should not, under any circumstances, affect the performance of embedded software;

- In the context of the connected vehicles that require driver, protection mechanisms should only request user interaction in extreme cases so that their attention is not diverted;

- Physical Condition: the ECU should be able to withstand high temperatures, fluids and debris impacts, due to the environment to which they are submitted;

- Life cycle: the technological apparatus of a connected/autonomous vehicle should be designed to allow upgrade process with ease, preventing obsolescence of the security mechanisms, since the life cycle of a vehicle is much larger than a traditional computer;

- Compatibility: must be interoperable with other devices and vehicles, as well as compatibility with the technologies currently in use.

External Communications Protections

Most of the vulnerabilities would cease to exist if were followed good development practices concerning security in communication protocols. However, as it increases the number of ECU suppliers, it is virtually impossible to guarantee that all will comply with the specifications. Thus, the integration of additional measures is essential, to ensure secure communications. There are European projects, such as Preserve (2011) and EVITA (Henniger et al., 2009) fruits of partnership between manufacturers and academic institutions dedicated to scientific research, for the development of a secure architecture for internal and intervehicular communication.

Internal Protections

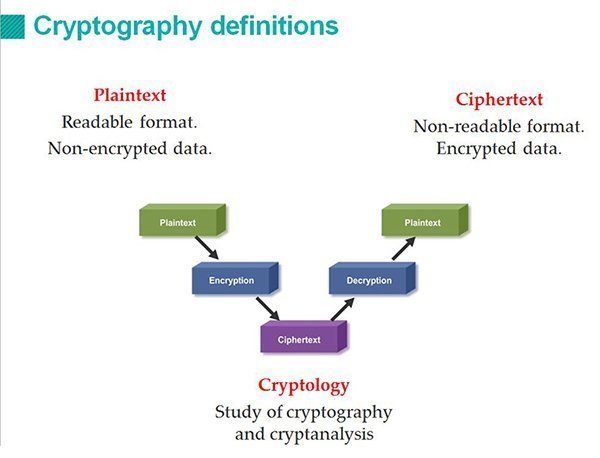

Criptography

Encryption allows operations as ECU authentication (proving that the message came from a trusted sender), integrity checking and encryption of content, preventing the reading for those who do not have the required keys (Van Herrewege, Anthony, Dave Singelee, and Ingrid Verbauwhede, 2011). However, these operations require high processing. To overcome this issue, it is suggested the creation of a dedicated encryption module by removing the load of this process from the other ECU.

Anomaly Detection

The goal of these measures is to check the legitimacy of data traffic between the ECU. It was proposed to create a tool that inserts a mark in the packages used by the ECU, as they are executed and transmitted, it is possible to identify the source of the malicious commands (Schweppe, Hendrik, and Yves Roudier, 2012). Other researchers have opted for the approach to intrusion detection, similar to IDS (Intrusion Detection System) of traditional computing.

ECU software integrity

It is extremely important to ensure that the software contained in ECU does not suffer alteration by malicious individuals. One way of achieving that is similar to what is done in the boot area of computers. Additionally, the isolation areas can be adopted, leaving the external communication modules in separate virtual machines to the critical software. Thus, even if the attacker can exploit a vulnerability in wireless network protocol, he can not commit to ECU as a whole (Arbaugh, William A., et al, 1997).

Conclusion

In this work, were presented the risks to which users of connected/autonomous vehicles are subject, as well as protective measures recognized as imperative to mitigate them. Considering what the attacks have demonstrated, we saw the need for greater attention by manufacturers to protect not only the information contained in the vehicles, but also the most important asset of the human being: his life.

Autonomous vehicles adds a new modal to existing transportation options and has the potential to revolutionize the automobile market, as they can promote the use of shared cars. Something similar to what is already happening with the alternatives to taxis, if we consider what companies like Uber provided.

When this technology became robust and mature enough, certainly will appear a lot of applications.

References

ABNT. NBR ISO/IEC 27001 – Tecnologia da informação – Técnicas de segurança – Sistemas de gestão de segurança da informação – Requisitos. Rio de Janeiro. ABNT, 2013.

Arbaugh, William A., et al. “Secure and reliable bootstrap architecture.” U.S. Patent No. 6,185,678. 6 Feb. 2001.

Blommendaal, Chris. “Information Security Risks for Car Manufacturers based on the in-Vehicle Network.” (2015).

Checkoway, Stephen, et al. “Comprehensive Experimental Analyses of Automotive Attack Surfaces.” USENIX Security Symposium. 2011.

Courtois, Nicolas T., Gregory V. Bard, and David Wagner. “Algebraic and slide attacks on KeeLoq.” Fast Software Encryption. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2008.

Davis, Robert I., et al. “Controller Area Network (CAN) schedulability analysis: Refuted, revisited and revised.” Real-Time Systems 35.3 (2007): 239-272.

Eisenbarth, Thomas, et al. “On the power of power analysis in the real world: A complete break of the keeloq code hopping scheme.” Advances in Cryptology–CRYPTO 2008. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2008. 203-220.

Forbes. 2015. Available in: http://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2015/01/27/connected-cars-by-the-numbers-infographic.

Makowitz, Rainer, and Christopher Temple. “Flexray-a communication network for automotive control systems.” 2006 IEEE International Workshop on Factory Communication Systems. 2006.

Gartner. 2015a. Available in: http://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/2970017.

Gartner. 2015b. Available in: http://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/3114217.

Glancy, Dorothy J. “Privacy in autonomous vehicles.” Santa Clara L. Rev. 52 (2012): 1171.

Hayat, Zia, et al. “Information security implications of autonomous systems.” Military Communications Conference, 2006. MILCOM 2006. IEEE. IEEE, 2006.

Henniger, O., et al. “Securing vehicular on-board it systems: The evita project.” VDI/VW Automotive Security Conference. 2009.

Koscher, Karl, et al. “Experimental security analysis of a modern automobile.” Security and Privacy (SP), 2010 IEEE Symposium on. IEEE, 2010.

Nilsson, Dennis K., and Ulf E. Larson. “Simulated attacks on CAN buses: vehicle virus.” IASTED International conference on communication systems and networks (AsiaCSN). 2008.

Preserve. 2011. Available in: https://www.preserve-project.eu/about.

Schweppe, Hendrik, and Yves Roudier. “Security and privacy for in-vehicle networks.” Vehicular Communications, Sensing, and Computing (VCSC), 2012 IEEE 1st International Workshop on. IEEE, 2012.

Van Herrewege, Anthony, Dave Singelee, and Ingrid Verbauwhede. “CANAuth-a simple, backward compatible broadcast authentication protocol for CAN bus.” ECRYPT Workshop on Lightweight Cryptography. Vol. 2011. 2011.

Wired. 2015. Available in: http://www.wired.com/2015/07/hackers-remotely-kill-jeep-highway.

Wolf, Marko, André Weimerskirch, and Christof Paar. “Security in automotive bus systems.” Workshop on Embedded Security in Cars. 2004.